Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University with collaborators at the University of Oregon and Manchester Metropolitan University have found a way to tease hydrogen out of the ocean by funneling seawater through a double-membrane system and electricity. Their innovative design has proven successful in generating hydrogen gas without producing large amounts of harmful byproducts. The results of their study, published today in Joule, could help advance efforts to produce low-carbon fuels.

Hydrogen gas is a low-carbon fuel currently used in many ways, such as to run fuel-cell electric vehicles and as a long-duration energy storage option—one that is suited to store energy for weeks, months or longer—for electric grids.

Many attempts to make hydrogen gas start with fresh or desalinated water, but those methods can be expensive and energy-intensive. Treated water is easier to work with because it has fewer substances—chemical elements or molecules—floating around. However, purifying water is expensive, requires energy, and adds complexity to devices, the researchers said. Another option, natural freshwater, also contains a number of impurities that are problematic for modern technology, in addition to being a more limited resource on the planet, they said.

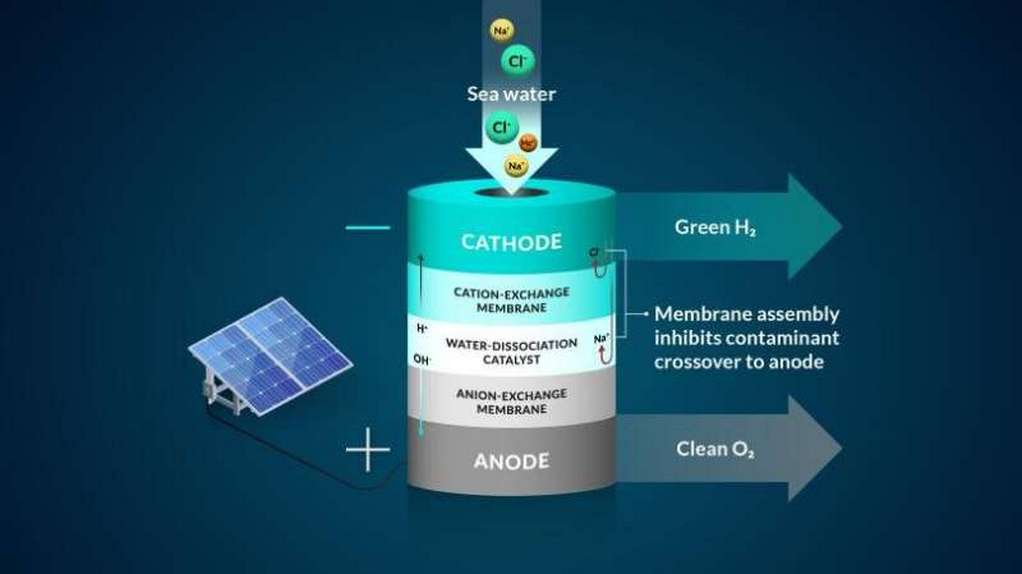

To work with seawater, the team implemented a bipolar (two-layer) membrane system and tested it using electrolysis, a method that uses electricity to drive ions, or charged elements, to run a desired reaction. They started their design by controlling the most harmful element to the seawater system—chloride—said Joseph Perryman, a SLAC and Stanford postdoctoral researcher.

The bipolar membrane in the experiment allows access to the conditions needed to make hydrogen gas and mitigates chloride from getting to the reaction center.

Researchers collect seawater in Half Moon Bay, California, in January 2023 for an experiment that turned the liquid into hydrogen fuel. From left: Joseph Perryman, a SLAC and Stanford postdoctoral researcher; Daniela Marin, a Stanford graduate student in chemical engineering and co-author; Adam Nielander, an associate staff scientist with the SUNCAT, a SLAC-Stanford joint institute; and Charline Rémy, a visiting scholar at SUNCAT. Credit: Adam Nielander / SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

An ideal membrane system performs three primary functions: It separates hydrogen and oxygen gases from seawater; helps move only the useful hydrogen and hydroxide ions while restricting other seawater ions; and helps prevent undesired reactions. Capturing all three of these functions together is hard, and the team’s research is targeted toward exploring systems that can efficiently combine all three of these needs.

Specifically in their experiment, protons, which were the positive hydrogen ions, passed through one of the membrane layers to a place where they could be collected and turned into hydrogen gas by interacting with a negatively charged electrode (cathode). The second membrane in the system allowed only negative ions such as chloride to travel through.

As an additional backstop, one membrane layer contained negatively charged groups that were fixed to the membrane, which made it harder for other negatively charged ions, like chloride, to move to places where they shouldn’t be, said Daniela Marin, a Stanford graduate student in chemical engineering and co-author. The negatively-charged membrane proved to be highly efficient in blocking almost all of the chloride ions in the team’s experiments, and their system operated without generating toxic byproducts like bleach and chlorine.

Along with designing a seawater-to-hydrogen membrane system, the study also provided a better general understanding of how seawater ions moved through membranes, the researchers said. This knowledge could help scientists design stronger membranes for other applications as well, such as producing oxygen gas.

Next, the team plans to improve their electrodes and membranes by building them with materials that are more abundant and easily mined. This design improvement could make the electrolysis system easier to scale to a size needed to generate hydrogen for energy intensive activities, like the transportation sector, the team said.

The researchers also hope to take their electrolysis cells to SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), where they can study the atomic structure of catalysts and membranes using the facility’s intense X-rays.

Recent Posts

Power & Propulsion Technology

Alfa Laval and Wallenius to form joint venture AlfaWall Oceanbird for wind-powered vessel propulsion

Power & Propulsion

Mitsui E&S, TGE Marine Open Dialogue with DG Shipping on Engine and Gas Systems Collaboration

Bunkering Methanol

UK’s first commercial biomethanol bunkering service launched at Port of Immingham